Regie:

Bernardo BertolucciDrehbuch:

Bernardo BertolucciKamera:

Aldo ScavardaMusik:

Ennio MorriconeInhalte(1)

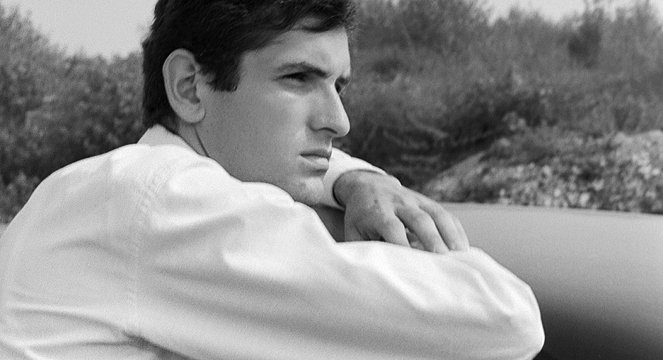

A rarely seen early work from one of world cinema's most acclaimed directors, Bernardo Bertolucci's beautiful and unique Before the Revolution - made when he was just 22 captures the passions and ideology of the 1960s. Young, idealistic and bourgeois, Fabrizio struggles to come to terms with these contradictions and master a transgressive love for his aunt. Part autobiography, part literary adaptation, part homage to the French new-wave and Italian neo-realists that inspired him, Bertolucci's virtuosic second film is an atmospheric, ambiguous portrait of idealistic youth. (British Film Institute (BFI))

(mehr)Videos (1)

Kritiken (3)

PCI receives about a quarter to a third of all votes in elections, while the native Parma securely lay in the red fortress of Emilie-Romagna. It is the 1960s - three out of four intellectuals are leftists and May 1968 is approaching. The youths of the Italian and European bourgeoisie, raised by universities, await the revolution. However, as Bertolucci showed us, the middle class became, for a certain period of time, at best a mere compagnon de route (a companion on the journey) of the proletariat, from whom it soon distanced itself: the main character stands in the middle of a quarry, surrounded by naked bathing working-class boys, wearing a suit. During the time of this film, Bertolucci believed that he correctly captured the weakness of his generation and especially his class in a position of engagement in a matter that negates it through revolution. The isolation of the bourgeois individual (sex within the family only strengthens the idea of the inviolability of their class) incapable of establishing a real connection with the working class, on whose behalf he acts (for example, his connection with the proletariat passes through the mediation of an ambivalent character of a teacher, who is introduced to us in the narrative as an enlightened active individual, but on the screen later appears as a dull passive figure, equally isolated and living in the past). However, Bertolucci did capture, which only we can know retrospectively, the greatest tragedy of left-wing intellectuals or artistic filmmakers: the Godardian motto of style as a moral (political) choice, which Bertolucci explicitly puts into the mouth of one of the characters, concealed the belief of the impatient European bourgeoisie that revolution is a conscious negation of the world - a new form, a new way of thinking, and new editing. That is certainly true, but it forgets about the long, tedious, and surface material struggle. History has taught us that the spring breeze of May quickly subsided, new waves came and dissolved, the bourgeoisie found cozy spots, and Bertolucci started making Hollywood films. /// However, the muse of Revolution will give birth to beautiful unrest again and a fresh new perspective, as Bertolucci's early films demonstrated.

()

Again, one of those movies that are heavily influenced by Europe and its unique, less plot-driven style, which personally bothers me quite a bit, I can't get into it. I like poetry, I like more meaning, but I like plot even more, and these movies just don't give me that. It can be as artistic as it wants, but it just doesn't impress me.

()

With his second film, Bertolucci returned to his native Parma in order to tell about the spiritual wanderings of a young man who lacks the courage to leave his petite-bourgeois certainties and step out into life. Anchored in the present, which paradoxically becomes the object of his nostalgia, he lives constantly BEFORE the revolution, perhaps out of fear that his life will lose direction after the revolutionary act. Fabrizio’s own aunt becomes a seductive challenge to disrupt the order. The depiction of an incestuous relationship and the soul of a man torn apart is significantly more playful than in the sombre Fists in the Pocket by another left-wing director of the same generation, Marco Bellocchio. That doesn’t mean that Bertolucci sympathises with the protagonist and lends him the main word. On the contrary, he uses many narrative perspectives and numerous alienating devices to draw our attention away from the protagonist’s suffering and put the focus on the cinematic form. The disruption of the linear flow of the narrative with discontinuous jumps in time and structurally unjustified interpolations (even in colour, for example), the Resnais-esque interweaving of subjective memories with objective reality and the Godardian omission of film frames reveal the young filmmaker’s tremendous playfulness and great cinephilic knowledge. We can perceive the stylistic contamination as evidence of how strongly Bertolucci was influenced early in his career by Pasolini, another intellectual who gladly combined sex and politics, classical and modern, the secular and the profane (and, like Bartolucci in Before the Revolution, cast non-actors in his films). When we start to notice the similarities between this film’s plot and that of Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, the question arises as to whether Before the Revolution offers anything original at all. I would say that the obviousness and ostentation with which it borrows from others are what make this film a timeless work, prepared for the rise of postmodernism. 75%

()

Werbung