Kritiken (536)

Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert (1976)

Images without characters and houses long abandoned. A camera floating over words about human fates in a deserted landscape of past lives. A double death, the triple death of characters: only their voices occasionally echo in the backdrop of their demise; only the voice of the narrator, who often takes over for them, lets their passions and suffering be heard, about them and without them. Without them, and yet their presence constantly screams - no character ever appears in the image, but no image ever says anything else than that they lived here and were the same characters. Duras is a master of nostalgia for people who are still, which now reveals that these people were condemned to the demise of their love, their efforts, their life, their colonial bourgeois and environment longing for aristocratic shine, condemned by themselves and others, condemned while alive and thus already dead – that is why they can speak even after their end - because the beginning already belongs to their death. It is joyful to watch only the camera and not perceive the sound, and it is joyful to just listen and not perceive the image; it is joyful to do both at once. And yet, or precisely because of that, they will never fully merge.

Az ötödik pecsét (1976)

A human face fascinated by a piece of meat, which will soon transform into it. Will it be transformed by the hands of fascist butchers or by its own hand? We must admire how Fábri was able to capture this transformation with the claustrophobic grip of a dimly lit camera in the first part of the film. The question of how to properly handle meat is not as difficult as whether it is worse to become a piece of meat passively enduring its fate under the butcher's knife or to become an emotionless master of the world. The film shows that neither position is morally superior. The constant reversal of moral superiority shifts guilt and bliss of conscience from one character to another, only for the one who most consciously approaches the position of a slave with a clear conscience, unburdened by the weight of the world, to become the most despicable informant, and for the uninvolved cynic to become an unknowing supporter of the life force for others, which he had to deny at first glance in order to gain it. It is as if moral opposites were not different in anything, not even in the fact that "evil" lies in "consciousness."

La Proprietà non è più un furto (1973)

A sad comedy that robs the viewer of hope and in which no one is happy. When the principle of theft is privatized and stealing becomes a universal imperative, a den of thieves is created in broad daylight, enlightened by self-interest and the natural right to inalienable private ownership of public institutions - the police, law, and banks. When a thief pursues you in such a situation, you are pursuing yourself. After his political thriller and social drama, Petri attempts to awaken the viewer's conscience with a political comedy, and many moments or stylistic elements will remind them of his previous attempts, interconnected with this film's deeper left-wing critique of bourgeois society: reminiscences of Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970) in the cool editing and precise camera work, with the sounds of Morricone's music in numerous night scenes, and with the main protagonist's father figure being almost functionally identical to the same character (played by the same actor, Petri’s favorite Salvo Randone) from The Working Class Goes to Heaven (1971).

Faust 6 (2011)

The greatest strength of the film is its greatest weakness: the counterpoint of matter and spirit, body and soul. The materiality of the body brilliantly intrudes into Sokurov’s otherwise typical slow flow and into lyrical classical/preromantic images. The repulsive bloated body of Mephisto amidst female purity in the beginning; Margarete’s beauty gradually ending in a shot of the vulva: the symbol of the gradual disturbance of the balance between soul and body, and the reduction of what is noble in a man (his disgust for God) to an animal (non)essence. Who introduced imbalance and Sin into the world of balance between soul and body? Who abandoned patient asceticism of knowledge, and who exchanged the promise of a constantly advancing future of science for one night with Margarete? The answer is also the answer to the question of why this typically religious interpretive framework is the film's greatest drawback: unlike Goethe's masterpiece, it completely flattens Faust's story into a Manichaean struggle between soul and matter - only Mephisto can come from the body, matter, and sex. Faust is no longer a self-destructive hero who has already achieved everything in knowledge and who joins forces with the devil to know even more, and thus he must also know what escapes science. Now he is just an impatient and defeated renegade of spiritual work, who succumbed to desire and ended up in a barren desert on his journey for bodily pleasures, which means the death of the body and the spirit. Sokurov's Days of Eclipse also took place in a desert, but the direction was the opposite: detachment from a filthy reality led upwards... here, falling away from God is inevitable. Therefore, the review must also be less.

Der Sprung ins Leere (1980)

If anyone is interested in what (not only Italian) bourgeoisie could be like, that bourgeoisie, as depicted in the cinema of the 1960s by Antonioni, Bertolucci, and Bellocchio after ten or fifteen years, that is, after reaching middle age, should watch A Leap in the Dark. When Antonioni and co. revealed the breakdown of communication and isolation among modern individuals, they showed them still in their youth. In 1980, Bellocchio shows a portrait of the modern bourgeoisie that is even more unbearable because the middle-aged bourgeoisie not only failed to overcome mutual alienation but also, as a result, failed to mature. Hence the complete infantility of the characters: at the beginning of the commentary, I wanted to use a journalistic shortcut to say that this film is like if the characters of Monica Vitti and Alain Delon from The Eclipse got married, "with the footnote that this is a relationship between brother and sister." However, this film proves precisely that the "footnote" is not just an addition and something in parentheses but that it is a necessary condition and necessary consequence of Antonioni and co.'s films. Therefore, the bourgeois characters must remain closed in the infantile isolation of childish games; neurosis and absolute inner weakness, compensated only by external imitation of social behavior or education, must be shattered by the mere presence of a real child, which brother and sister will never conceive, and therefore neither will all bourgeoisie. Impressive performances by M. Piccoli and A. Aimée.

Les Hautes Solitudes (1974)

The film Law of Solitude. There’s always only one face in one shot. A person is alone in the film window, and the shot is alone in relation to all the other shots. Trying to find continuity between the shots would mean simultaneously tearing the characters from their solitude because the story already creates a connection between multiple shots, resulting in the interconnection of characters within a common time and space. This does not happen. Seberg has her frame, and Aumont has hers. Only Terzieff duplicates himself in the mirror. The only case when there are two faces on the screen at the same time is the perfection of illusion. Every viewer who would want to find a story in the film and thus defeat loneliness will find no clue in the film and no legitimate justification for their heroic act: they will be on their own.

Organism (1975)

Film as a tool of cognition, an experimental film/epistemology merges with the aesthetics of accelerated image. Through this acceleration, knowledge itself speaks to us: under the effects of time-lapse, the everyday flow of time evaporates, revealing its unconscious structure. More precisely, its unconscious conditions of possibility, the structures that persist - unlike ordinary consciousness, which flickers so quickly that it is blind to the structures that give birth to it, causing our conscious self to think, like a child covering its face and thinking its mother cannot see it, that it gives birth to the world and to itself. Hilary Harris, like Marie Menken in Go! Go! Go!, dissolves the individual in their organism (whether biological or social) and, in the best traditions of structuralism, shows that the individual subject is nothing more than a secondary product of structure: Did you see a "Man" in any of the shots? I only saw structures, elevated to the place of that "Man" - they become the subject, they live, they grow; they decide where the human mass, frenetically accelerated by the film macro lens, will go: people are just blood in a giant organism, which they themselves unknowingly create daily, and which, as we must realize, human individuals create without needing them in their individuality.

Week-End (1967)

Can the bourgeoisie distinguish between erasing the difference between the nightmare of their "post-industrial" desires and the reality - a reality in which the difference between the tearing apart of a human body and the tragic death of a Hermès bag is blurred? Can the leftist filmmaker distinguish his film from a similar perverse imagination that he displays in the introduction of the bourgeois characters he created? The bourgeoisie fantasizes about debauched sex with eggs and milk, while the anarchic guerilla boils people in the end, mixing them with eggs or pork. Therefore, Weekend is not yet a fully political film by Godard - it is still self-ironic and sometimes ambiguous. It is rather a dirty dream of a leftist who bestows it with supreme cinematic art on the characters he himself invented to satisfy his desires. But just like any fantasy, this one also has its origin in the reality it reacts to, i.e., the total degradation of man by consumption and money. To this, the film/leftist dream responds with a total massacre, anarchic self-destruction of the world that rejects and devours itself without an exit (about a year later, Godard will find an exit: Mao's yellow submarine). Otherwise, it is a brilliant combination of absolutely clear motifs and scenes (the entire film is accompanied by Godard's love for slapstick humor) with the most artful alienation from everything clear (back then).

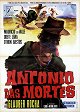

Antonio das Mortes (1969)

The era of cangaceiros - the bandits of the sertao, the arid northeast of Brazil - has ended. It not ending because it has already ended: in the film, the characters move deliberately as if lifeless (the burned-out Antonio, whose raison d'être perished by his own hand; Coirana, who is merely a follower of a dead bandit tradition and in the film only literally dies from a certain point onwards; the blind old landowner, foolishly defending his property, a typical character of perverse dehumanizing greed against the green of life, etc.). Rocha can better build the brand of his work in this way: the intertwining of reality and myth, characters mythologizing themselves, the transformation of real misery into a mythical reflection, etc. Moreover, the intertwining of counterpoints is repeated in other narrative elements: in the mise-en-scène, for example, when Antonio and the bandit Coirana meet (a meeting so quick compared to Black God, White Devil..., where we waited for it the whole film), and in which the characters unexpectedly blend in one long shot, until suddenly they face each other, but also in the scenes when Antonio (dressed in early 20th-century clothing) stands amidst modern car traffic. Cars speeding by, indifferent to the characters of the movie. This is the main counterpoint and the main message of the film: the myth of cangaceiros is dead, times have changed; the myth of yesterday is not an inspiration, but precisely a juxtaposition with today. The struggle of today only comes when the last myth of yesterday dies and becomes just a memory, and only then can it strengthen those who are going in the same direction as he once did. This is the engaged message of the film, personified in the character of the "Professor": just like Antonio, he joins the side of the people only after Coirana's death. So, what does the awakening of the mercenary Antonio mean? In my opinion, it is a clear parallel to the situation in Brazil at that time and the rise and consolidation of the military junta in the late 1960s: Can't Antonio's awakening (the soldier) and his alignment with the Professor (Rocha's left-wing intellectual type) against the blind landowner serve as an appeal to the army to join the side of Brazilians and turn against the isolated bourgeois/landowning elite?

Totò che visse due volte (1998)

A spiritual and more humorous successor to films like One Man and His Pig by Zéno and Begotten by Merhige - a total desacralization and destruction of all fantasies about a higher existence of human life, concretized as religion as with Zéno, which grows here as well as there from the most animalistic foundation of a human being as an animal and is nothing more. Masturbation as a principle of life: the masturbation of a pubescent panicking in anticipation of sex with a woman and fantasizing about how great it will be, just like adults always wait for the arrival of love, the messiah... The authors stretch this masturbation moment, turning adult actors into pubescent figures, dreaming of big breasts (maybe those from Fellini's Amarcord?)... Above all, through the absence of any real women (except for desexualized old women who, moreover, are also played by male actors during the film /perhaps without exception?/), they show how a woman and the Virgin Mary are only the product of a "pubescent" male brain. Unlike the two aforementioned films, which, even from the depths of their materialism, evoke a feeling of tragedy, horror, or sadness in the viewer about the human condition, "Totò..." (of course, the name of the famous Italian comedian) with its comedy prevents any feeling of nobility and is therefore much more unbearable than, for example, the unbearably brutal shots of a human reduced to a piece of meat in Begotten. However, the film does offer beautiful cinematography, it must be said - yes, that is also the only thing that remains when you discard the nonsense of all the content...