Kritiken (536)

La classe operaia va in paradiso (1971)

When you look into the abyss, the abyss also looks into you. And when you spend eight hours a day looking at a machine, the machine becomes a part of you. Petri, especially in the first half, outlines a brilliant study of the mutual interaction between the worker and 'his' machine. Lulu takes seriously the time when it is no longer enough to be just an appendage of the machine, but you also have to love it - the machine and its rhythm become a place where he lets out his frustrations, realizes his desires, and becomes the best among others. Without thinking, he was able to concentrate on the monotony of the machine and didn't notice that its rhythm had directly transferred to him. And Lulu, portrayed by Volonté, just like in Petri's previous film, is a character on the edge of madness. The necessity to adapt to the regularity of the factory world is the same as adapting to life in a mental institution, with the difference being that the insane person sees the wall separating them from the world, but the worker does not, only building it brick by brick around his assembly line and eventually within himself. What about when he tries to resist the rhythm, to not keep up? As long as you give everything to the machine, it also gives you something in return, but when you only give it a little of yourself, it takes everything from you. The worker has a finger to sacrifice at any time, while the “padrone” has a finger to show you where your place is.

Der schöne Mai (1963)

It looks seemingly simple: just go out on the street and engage in a conversation with a willing Parisian, talk to them using gentle maieutics (the film could be called "Le joli maïeutique"), film everything with cameramen who know that documentary shots don't have to mean just sticking a camera on a tripod into the ground and then focusing on the talking head, and finally, refresh the film with a few deeper thoughts for contemplation. But because over 50 years have passed and no one has yet truly followed up on this work in terms of quality or scope, it speaks of everything that stood before the authors as far as the simplicity of the task is concerned. The film complemented the emerging (French) cinema-verité movement in its time, especially the famous Chronicle of a Summer by the Rouch/Morin duo. The soul of France, traced on the streets of Paris, shedding its burdens of the past and searching for a different future. P.S. The original version of the film is approximately 160 minutes long, but the English version (originally for the USA) was edited down to just under 2 hours. Some important scenes were cut, especially those with political significance (such as memories of torture during the Algerian War).

Le Bonheur (1965)

The cliché about the unity of content and form in all its beauty proves that it is not actually cliché at all. That is if someone has a filmmaker's sense like that of Varda. The plot itself is not particularly dazzling until we are dazzled by the colors of the film images, and it is precisely those colors that color the entire film. They are not just an aesthetic decoration, as they also play a role (and perhaps even mainly!) in the realm of meaning. The game played between several main colors (yellow, green, blue, red) forms the axis of the film on many levels. First, there is the symbolism that each color gains from its relationship to the environment and objects on which it appears (Example 1 red = during a conversation with the mistress in a café, there is a red sign in the background that says "temptation," but in the transitions, there is a sign on a red façade that says "trust," and in the next shot, there is a "certainty" sign on a white wall - followed by a cut to the wife in red and white clothes; Example 2 blue = the mistress' blue dress, the blue predominant in the city where the protagonist is leaving his wife). Colors also carry meaning in connection with the characters who become their carriers. The prevalent blue of the mistress gradually shifts to the male lover throughout the film. Blue (a symbol of the city) increasingly blends into green (a symbol of nature and also a place of family happiness in almost bucolic scenes). Yellow (here the color of "happiness" and traditionally the color of betrayal) - compare the final scene with the mistress in a yellow sweater to the first scene of the film with the wife in the yellow dress (i.e., predominantly yellow with elements of green and red; in terms of colors, we must be precise here!).

Tema (1979)

Two distinguished men of letters set off, naturally in a dark Volga car, to the countryside. They, of course, go to a cottage (complete with a color TV and a telephone). Rows of awards and public respect are a given, as are honorary memberships in artistic organizations. One of the men is already looking forward to a meeting with the bottle, to a comfortable bourgeois life in the socialist country, which has triumphed over a challenging time of uncertainty, and the time of effort and growth is far behind them, like the war. The other has not forgotten that there used to be something more within him, and he suspects that the root of life has not yet completely grown over with comfortable job security. It is a typical Russian example - beneath the sarcastic and bitter shell washed with vodka and resignation, dissatisfaction boils. He tries to find a way out (back), and whether it is initially curiosity, it then becomes vanity, and maybe eventually love - the attempt plays out through his muse. It is more so an intimate film, but one that hides more than it seems (for example, a total of 4 types of artist life – the conformist, who creates for a living; the "martyr" who is willing to sacrifice himself or his social status for his art (here, a peasant poet); and the uncompromising but proud artist, who wants to celebrate his work and himself (here, a gravedigger-emigrant). Finally, there is the main character, consciously or unconsciously striving for quality work and recognition, and as the typically Russian optimistic ending shows, it is impossible to reconcile all things...).

Zachar Berkut (1971)

The story takes place in the first half of the 13th century on the western edge of the disintegrating Kyivan Rus. The film can be divided into three parts (half an hour each): the second part is perhaps the most interesting, reflecting the real historical situation of the collapse of early medieval family structures in favor of high medieval feudal relationships between lord and vassal. This part is also spiced up by the historically accurate "collaboration" of the emerging feudal class with the Tatar "occupiers." The third part is a straightforward and simple (but not bad) clash between defenders and attackers. Why didn't I start with the first part? Because it's unnecessary and, most importantly, the weakest of the three. It's half an hour dedicated to witnessing the birth of love between the daughter of a treacherous boyar and a heroic figure from the "Ukrainian" defenders' camp. This Tristan-esque motif is not further developed in any interesting ways and only serves to slow down the rest of the film.

Klassenverhältnisse (1984)

The titles of artworks cannot be underestimated. When we focus on a film, for example, Griffith's title Intolerance is the only explanation and connection for the whole three-hour film. Here, the change in the title shifted our perception of the entire work: from a vague existential "The Vanished" it became a story about alienation in modernity with its specific discovery - dehumanized working relationships, in which all other human relationships find their faithful reflection. Instead of a general statement about the absurd anonymous situation of contemporary people in an ever-growing world, with more and more helpless individuals, we are presented with a no less pessimistic story, but now with a clear example of one of the manifestations and causes of this state - the emptiness of human relationships breeds a chase for class privileges, clinging to one's own position, and humiliating subordinates, which in turn builds even greater walls between people. Kafka thus becomes a socially critical writer from the non-general, non-philosophical side of things. After all, Therese’s narrative almost seems to have come out of a socialist realist novel from the early 20th century; Karl's "trial" is thus different from that of Josef K., as here it is a process of being fired from work, but no less absurd and hopeless for the accused. The formal simplicity allowed the authors to preserve the spirit of the original work (in the novel, Kafka mainly describes human relationships and conversations, while transitions and descriptions of the surroundings play a lesser role, by which independent authors could additionally save on costs!).

Der Mann aus Eisen (1981)

It is a very well-made film, but isn't it strange that no one complains about ideological prejudice regarding the film? Strange. This is because the film is nothing more than a hagiographic tale of good and evil, a kind of inverted building film in which moral democratic life is constructed through dissatisfied workers instead of socialism and contented workers. When something is turned upside down, only the signs are exchanged, but the structure remains the same... What is present in building (communist) ideology and propaganda in films can be found here - in a situation turned 180 degrees - as a reflection of true history, of course. As a true Pole, Wajda clearly systematically tries to build legends about his nation through his films, which may impress Poles, but for people who see through the nonsense about "a life of truth," sanctioned by constant (idolatrous, morally burdensome for some) "in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit," this agitprop (also due to its length) can tend to not be a very pleasant experience.

Claires Knie (1970)

The film is truly more literary than cinematic, but Rohmer managed to conjure up a holiday atmosphere by the lake (Annecy in France, not Lake Geneva, by the way). The never-ending game of dialogue between the older and serious Jérôme (played by Brialy with cheery balanced certainty) and the scheming writer Aurora, or between Jérôme and his teenage stepsisters. The thoughtful and tolerant Jérôme does not perceive love as a binding duty, marriage as an act of self-compulsion and renunciation of other women, but rather as the voluntary desire of two people to stay together. This allows him to "get to know" other women as well. But where does freedom end and infidelity begin? Is it possible to justify short-term interest in others while having certainty that one long for only that one person and loves only them? Can we believe Jérôme's claim that his conception of love, which rejects any possessive approach towards the one he loves, really holds true, when the only real desire he could evoke in him after years was the holding = possession of one juvenile knee? Can we believe a person who claims that character matters more than physical appearance, when the prematurely intelligent and therefore charming sister does not awaken genuine "interest" in him, but rather the one he saw and observed before he even spoke to her?

Kesyttömät veljekset (1969)

Two young brothers and two different approaches to life, or rather to entering into it. The first, around whom the story mainly revolves, is already married and is trying to start his own small business. He embodies the "Protestant" capitalist morality, trying to make ends meet through sacrifice and hard work, but quickly realizes that it is difficult for small entrepreneurs to break through with wholesalers (because they can change the terms of an agreement during its course, as they already have long-term contracts...). His carefree brother, a university communist, on the other hand, devotes himself to the future of society and cultivating relationships with his girlfriend (the daughter of a big capitalist - the authors could have avoided this cheap trick...). The business eventually gets going successfully, but it turns out that what was supposed to be just a means to a happy family life has become the ultimate purpose, enslaving its presumed master, and reserving all the time for itself. Slowly but surely, it undermines the family itself... In the atmosphere of the late 1960s, the authors' attempt to not lean towards either side was evident as it was most likely a call for synthesis between capitalism and socialism, East and West, which "Finnishized" Finland could have been extraordinarily close to.

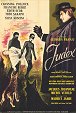

Judex (1963)

A tribute to Louis Feuillade and silent films of that time period. However, the displayed respect is not in any way shallow, it is not a mechanical transfer of Judex (the original 12-part series from 1916) into a world 50 years older, where people produce sounds when opening their mouths. The film is often self-ironic and intentionally nostalgic, with an attempt to remind us of or evoke in us the fairytale nature of the original. Nevertheless, it is a film made half a century later and it shows that the fairytale world depicted in films 50 years ago did not correspond to the actual fairytale world. The original was created during World War I. The fairytale on the screen was thus accompanied by a time period that was far from a fairytale. That is why Franju made a sad fairytale film. That is why we have both the funny detective Cocantin and the childishly mysterious masked hero, as well as heroes who die. That is why this is a fantastic story full of twists and a slowly flowing, almost melancholic pace. Thus, it did not result in a colorful (I don't mean the color of the film) remake, but rather a true tribute to Feuillade and his time.